There will be no members of the Muslim faith among the representatives in Myanmar’s next parliament.

The country’s largest Muslim party, the United National Congress, has conceded it will not win any of the seats it contested, and a handful of other Muslim candidates have also come up short.

Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy appears to be the overwhelming winner of Sunday's election, but fielded no Muslims as candidates, bowing to a Buddhist nationalist group that sought to taint the party in the eyes of the country's Buddhist majority.

The military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), which is facing a staggering loss in the national polls, also did not field any Muslim candidates.

Despite members of the religion being absent from the NLD party’s candidate list, long-standing support within Muslim communities for the party appears to have held.

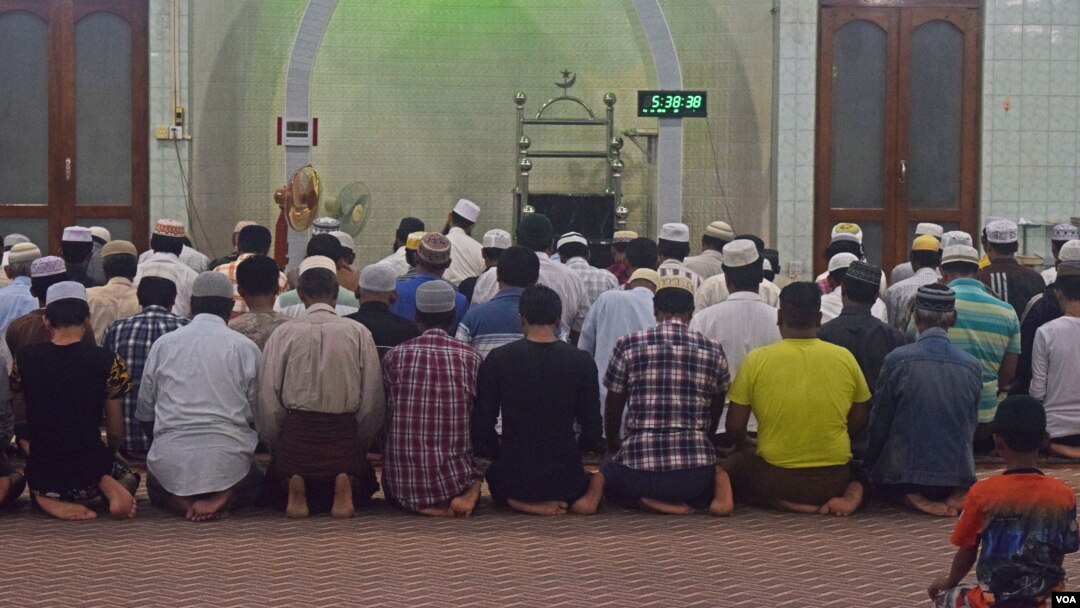

Myanmar Muslims are seen praying at a mosque in central Mandalay. (Photo - D. de Carteret/VOA)

Muslim Win Mya Mya, the NLD vice-chairperson for the central Myanmar region of Mandalay, intended to run for office, but was told not to by her own party because of her religion. She told VOA the decision was pragmatic in the face of widespread anti-Muslim sentiment in the country that casts Myanmar’s Muslims as interlopers intent on extinguishing Buddhism.

“I personally feel quite sad that there won’t be any Muslims in the parliament,” she said. “We were born here. I’m a citizen. I only speak Burmese. My grandmother and grandfather were born in Myanmar.”

But she said the NLD has the support of most Muslims because it is the only party that could pull Myanmar out of decades of military rule and improve the lot of ethnic and religious minorities.

“Many people know that only Aung San Suu Kyi can bring about big changes for the country,” Win Mya Mya said. “The Muslim people shouldn’t feel too upset that there are no Muslims in parliament because the NLD party can do a lot of things for all the people.”

Communal strife

But the party has an unclear stance toward the country’s stateless Rohingya minority, raising concerns an NLD government would be no better for Myanmar’s millions of other Muslims. The Rohingya were barred from voting in the election.

Achieving religious harmony will not be easy in a country where incidents of inter-communal violence have broken out since 2012.

Mandalay erupted in riots in July last year after a false allegation a Muslim man had raped a Buddhist woman. Fighting drove many people from their homes, including Muslim resident Yin Yin Moe and her family.

They were able to return home in three days after inter-faith dialogue between Buddhist monks and Muslim community leaders brought calm back to a city that has been multicultural since it was founded in the 19th century. But for too long, Yin Yin Moe said, authorities failed to intervene to protect her community.

NLD supporters eagerly await election results displayed on a big screen at NLD headquarters in Mandalay. (Photo - D. de Carteret/VOA)

“When the communal violence breaks out, we have to run away. We had to leave our house because we don’t have equal protection under the law,” she said.

Yin Yin Moe was hopeful that Aung San Suu Kyi’s repeated pledges to establish the rule of law in Myanmar could help prevent communal conflicts from spiraling out of control. But with some months until a new government can be formed, she said she is worried political uncertainty could invite further problems.

“The discrimination is not just the regime, it’s in the mind of some of the Burmese people,” Yin Yin Moe added. “She (Aung San Suu Kyi) can’t change that overnight.”

A losing candidate

Khin Maung Thein, the only Muslim candidate to run in Mandalay in this election, said he received only 815 votes in his race for a Lower House seat. The constituency is home to a large population of Pathi Muslims, who trace their roots back to Muslims who served as aides to Myanmar’s pre-colonial monarchs.

Mandalay's sole Muslim candidate, Khin Maung Thein, is seen reading a book in his home. (Photo - S. Lewis/VOA)

The NLD was confirmed as the winner of the seat, taking 81,593 votes, likely including a large number of Muslim voters. But Khin Maung Thein pointed out he beat the ruling USDP’s candidate for second place in some individual polling stations.

His candidacy was largely symbolic anyway, he confessed, and in that sense achieved its purpose in drawing attention to the difficulties facing Myanmar’s Muslims. “For me, it feels like I won,” he said. “Although I lost, the people know what I have done, and the world also knows about it.”