Editor’s Note: This story is the second in a three-part series that explores the history of the federal Indian school on the Western side of the Navajo Nation in Arizona -- and a man who taught there and in a nearby day school for more than two decades.

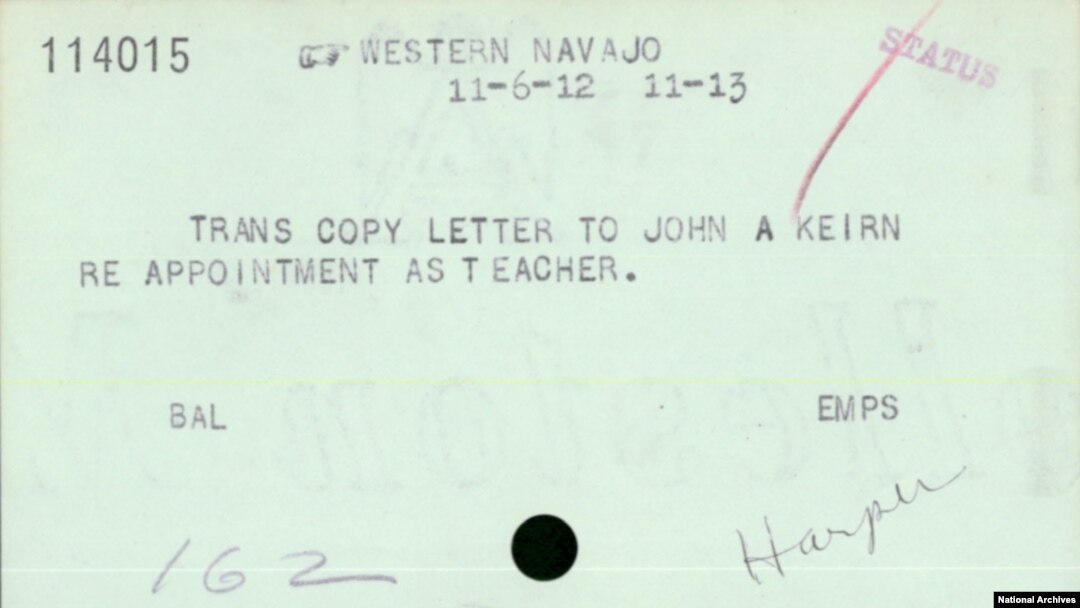

John A. Keirn was appointed a teacher at the Western Navajo Agency in Arizona, effective November 1912, earning $84 a month on a probationary basis, according to the Haskell Indian boarding school newspaper, The Indian Leader, which tracked appointments, transfers and retirements in the Indian Service.

Record of probationary appointment of John A. Keirn as teacher on the Western Navajo Agency in Arizona, effective November 6, 1912.

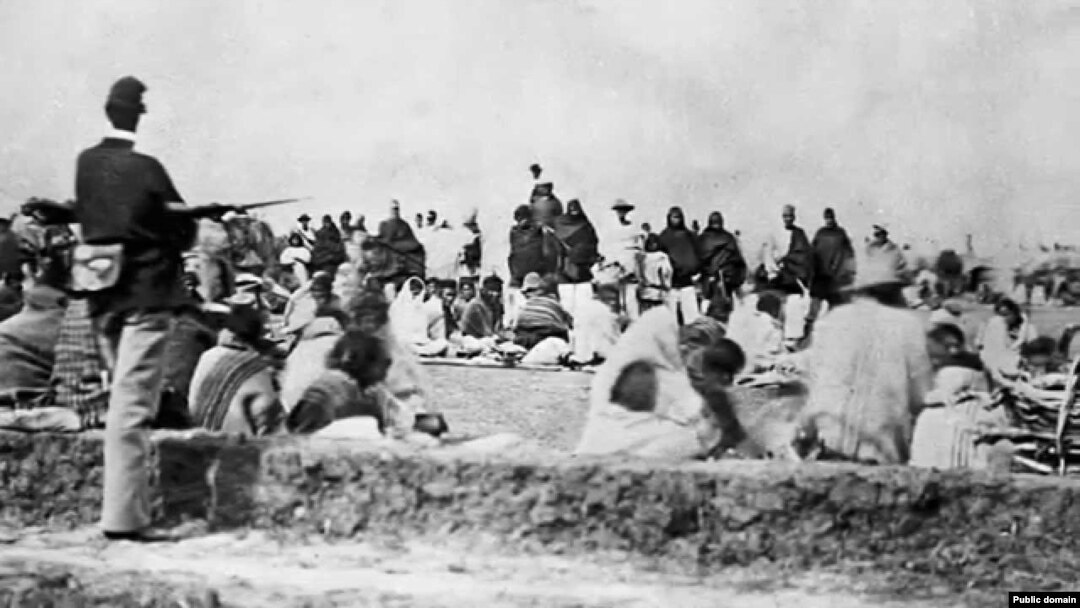

When Keirn arrived in Arizona, it had been 50 years since the U.S. Army began rounding up and force-marching groups of Navajo along the “Long Walk” to an internment camp at Bosque Redondo, along the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico.

The plan had been to turn the Navajo into farmers, but the experiment failed: crops failed repeatedly, conditions were bleak and the government, which was spending $1.5 million a year to feed the prisoners, finally relented and freed them.

Navajos under guard at Fort Sumner, built by the U.S. Army to watch over the Navajo camp at Bosque Redondo, ca. 1864.

In 1868, U.S. officials negotiated a treaty that established the Navajo reservation, which completely encircled the homelands of the Hopi. In 1882, Washington established the Hopi (then known as Moqui) reservation, which included a summer farming community at Moenkopi, 3 kilometers outside of Tuba City, which was part of the Navajo Nation.

Army campaigns against Native tribes in the Southwest ended with the capture of the Apache leader Geronimo in 1886; now, the U.S. turned its attention from warfare to forced assimilation.

Map showing boundaries of Navajo and Hopi Nations.

U.S. Army General Richard H. Pratt in 1878 had established the first of many federal off-reservation Indian boarding schools in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. By 1908, the government was operating 88 reservation boarding schools, 26 non-reservation schools and 165 day schools.

These included the Keams Canyon Boarding School for the Hopi (then called Moqui), which, like many boarding schools would come to be known by several names, and the Western Navajo Agency Boarding School, established at an abandoned trading post at Algert, in Arizona’s Blue Canyon.

When the government failed to make needed improvements to the Blue Canyon site, school staff, students and local Navajo stonemasons hauled stone and constructed their own school buildings.

The Original Western Navajo Boarding School was Rustic and Remote

“Oil-can cases were used for window frames and goods boxes were utilized for lumber to make doors, etc.,” the agency superintendent wrote in his 1901 report to the Commissioner for Indian Affairs in Washington.

In 1903, the government moved its Western Navajo Agency headquarters to Tuba City, an oasis fed by a tributary of the Little Colorado River. The city’s name belied its size; at the time, it consisted only of a trading post and a handful of buildings left by earlier Mormon settlers.

In 1904, the government began constructing a new boarding school to replace the Blue Canyon school: The new Tuba City Boarding School was comprised of three imposing buildings, arranged symmetrically in an architectural style typical of federal buildings at the time.

Undated photograph of Tuba City Boarding School showing students lined up for drill. Courtesy Tuba City Boarding School.

“Such an arrangement suggests both system and the authoritative, almost military-like, approach to education that dominated BIA thinking through the first two decades of this century,” reads a National Park Service survey of the buildings.

The children slept in “large impersonal sleeping rooms” that doubled as classrooms. As the student population grew, the agency added 40-bed sleeping porches to the boys’ and girls’ dormitories.

Gradually, the school expanded to include a classroom building, mess hall, steam laundry and employee living quarters. By the late 1920s, the campus included a 50-bed hospital, barn, garages and machine shop.

Page from U.S. Army Infantry Drill Regulations, 1911, with text corrections to February, 1917. Excerpts were used in the federal Indian boarding schools.

Bugles and drills

In her 1954 memoir “The Red Moon Called Me,” Gertrude Golden, a teacher in the Indian Service from 1901 to 1918, described student life in non-reservation boarding schools as highly regimented.

“The pupils were divided into companies according to age and size, and each company had its captain, lieutenants and corporals,” she wrote. “These officers drilled their companies in marching, setting-up exercises and simple military maneuvers.”

In his 1914 annual report to the Interior Secretary for 1913, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Cato Sells said that as a means to ensure uniform systems of drilling in these schools, “a pamphlet has been published for the use of employees reproducing a portion of the Manual for Infantry Drills now used by the United States Army.”

A former student at the Tuba City school would later recall: “In the morning, the bugle would blow, and all the children would go out and line up to salute the flag while the bugler played, and then they marched to the dining hall.”

Tuba City students earned their keep working on the school’s 200-acre farm, which included garden plots, a large apple and pear orchard, and about 40 hectares each of alfalfa and corn.

Students raised and butchered their own livestock, canned fruits and vegetables for the winter, and in cold months, harvested ice for summer.

View of Moencopi Village, 1914.

Sometime before 1920, my great-grandfather took a series of photographs (see photo gallery, below). These ended up in Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, which digitized them for VOA. Because the children are young, I assume that they were Hopi children attending the Moenkopi Day School.

Farm Training or Forced Labor?

Never made public before, the photos (above) are gut-wrenching: children, some of them not much older than 4 or 5, stand in the hot sun behind mounds of picked apples; boys lean on hoes amid rows of what appears to be lettuce.

One photograph shows the children holding Navajo rugs and popular monthly magazines like McClure’s, which would have been completely foreign to them, both in language and cultural content.

Not one child is smiling.

NOTE: Part Three of the series examines student health and nutrition.