A security pact signed this month with the Solomon Islands will clear a lane for the Chinese military to access the South Pacific despite opposition from the West, experts say.

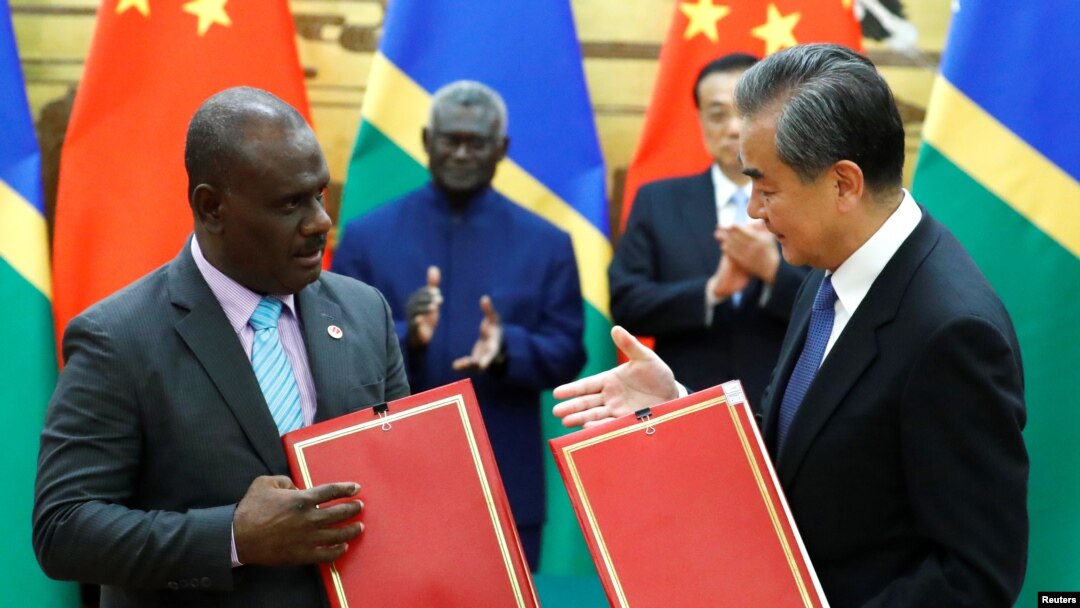

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said April 14 that Foreign Minister Wang Yi and his Solomon Islands counterpart Jeremiah Manele had signed the agreement.

SEE ALSO: China Signs Security Agreement with Solomon IslandsThe deal allows both sides to maintain social order and protect lives and property in the South Pacific archipelago, said Liu Pengyu, spokesman for the Chinese embassy in Washington. A draft of the deal said it would let China send armed forces and dock warships.

SEE ALSO: Solomon Islands Sign Security Pact With ChinaAustralia, New Zealand, Japan and the United States all expressed fears that the Sino-Solomons deal would smooth the deployment of Chinese military forces among the sparsely populated and often poor nations of the South Pacific after years of diplomatic efforts by Beijing, analysts say.

"Who initiated this agreement? If it was Beijing, then Beijing is trying to get a foothold in the Pacific, perhaps not in the form of a military base but in the form of an agreement that would facilitate the international extension of its security apparatus," said Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, associate Pacific Islands studies professor at University of Hawaii at Manoa.

China initiated the deal, according to White House sources.

Strategic region

The vast South Pacific, which extends from northeastern Australia to the waters off Peru, matters to China if it wants to be a global military force, said Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center, a Washington think tank. China has been building up naval strength beyond the seas near its coasts, as its rival the U.S. and other Western powers have done.

SEE ALSO: Chinese Navy Expands Presence in Asia"We know that currently China doesn't have the security alliances or the bases that would give China global power projection capability," Yun said.

Any Chinese base could incite strong dissent in the Solomons and in the West, Kabutaulaka said. China would find it hard to acquire land because most of it is communally owned by tribes, he added. But he said the lack of a base wouldn't stop Chinese naval ships from mooring in the Solomons and moving farther into the South Pacific.

Step by step

Per the security deal, police or military personnel could visit the Solomons at the South Pacific country's request, Kabutaulaka said.

That could mean helping Chinese citizens affected by rioting, he said.

Chinese business owners suffered "disproportionately" during riots last year and the unrest in 2006, said Denny Roy, senior fellow at the East-West Center think tank in Hawaii.

Chinese businesspeople are behind the Solomon Islands' logging industry, most retail in the country and the imports of daily necessities, Kabutaulaka said.

FILE - China's ambassador to the Solomon Islands Li Ming, right, and Solomon's Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare cut a ribbon during the opening ceremony of a China-funded national stadium complex in Honiara, April 22, 2022.

"You've got the premise of economic ties, and basically China is saying, 'In order to get those economic goodies, you have to allow us to send (our) police and armed forces to protect those resources,'" said Andrew Reddie, deputy director of the Berkeley APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) Study Center at the University of California.

Officials in smaller countries such as the Solomons often accept the premise, he said.

Chinese authorities sometimes use bilateral deals to target their own citizens. In 2017, for example, they arrested Chinese citizens in Fiji on suspicion of fraud.

China had sought a dual-use port facility in Vanuatu as well but killed the idea after media found out, the research organization Brookings said in a 2020 study. Beijing has sought deals for dual-use ports in the South Pacific on other occasions, Roy said.

China already has agreements with several South Pacific governments to allow Chinese fishing in nearby waters.

Ultimately, China wants to be seen as an offset to Western powers, said Fabrizio Bozzato, senior research fellow at the Tokyo-based Sasakawa Peace Foundation's Ocean Policy Research Institute. "Beijing is trying, and has succeeded, (in) installing itself into Australia's immediate Pacific neighborhood and taking up the role of alternative security partner," he said.

Overcoming opposition

In November, anti-government protesters in the Solomons called out concerns about the country's links with China, which the government had established in 2019. Peaceful protests escalated into riots.

SEE ALSO: Solomon Islands Leader Faces No-confidence Vote After RiotsIn Australia, a U.S. ally that's 2,000 kilometers from the Solomon Islands, the country's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said it was "deeply disappointed" by the security deal.

Compared with China, Australia has historically had closer ties with nations in the South Pacific. It has provided more funding to the South Pacific than any other country, Roy said. Sino-Australian relations are strained now by their own trade and political issues.

SEE ALSO: What Decade of Decline in Bilateral Ties Means for China, AustraliaAustralia fears that a nearby Chinese military base would be a "concrete threat to Australia's security," Roy said. New Zealand's prime minister questioned the reason for the security deal, and Japan's chief Cabinet secretary said it could upset regional security.

A White House National Security Council spokesperson accused China of "offering shadowy, vague deals with little regional consultation" in the South Pacific.

SEE ALSO: Why Are Solomon Islands Newest Battleground in US-China Geopolitics?

China's cooperation with the Solomons targets no other party, said Liu, the Chinese embassy spokesman. "While the Pacific Island countries such as the Solomon Islands can conduct security cooperation with Australia, New Zealand and Japan, they of course have the right to cooperate with other countries," he said.