The recent arrest of a renowned Harvard professor and pioneer in nanoscience sheds light on relationships between American brain power, the Chinese government and funding between the two that involves intellectual property theft.

Charles Lieber, head of Harvard University's chemistry department and a world leader in nanoscience, appeared in a jumpsuit and leg shackles in court in Boston on Jan. 28 when he was charged with lying about receiving funding from Chinese research agencies. Lieber was simultaneously receiving research funding from the U.S. Department of Defense and the National Institutes of Health.

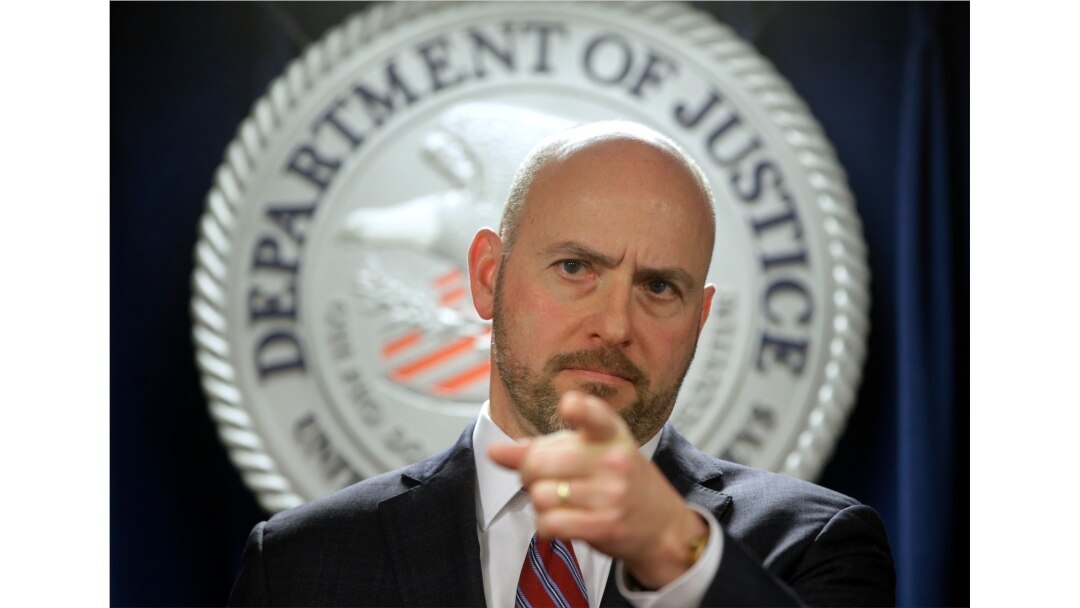

U.S. Attorney for District of Massachusetts Andrew Lelling announces indictments in a sweeping college admissions bribery scandal, during a news conference, March 12, 2019, in Boston.

The government alleges that Lieber hid being paid up to $50,000 a month by the Chinese government. He also received more than $1.5 million to create a research lab at Wuhan University of Technology in China, according to court documents.

“This is a small sample of China's ongoing campaign to siphon off American technology and know-how for Chinese gain," said Andrew Lelling, U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts in a press conference when Lieber was charged. Lelling led the investigation.

Thursday, U.S. Attorney General William Barr, FBI Director Christopher Wray and Lelling highlighted stepped up efforts to combat Chinese espionage at a conference in Washington, citing the relationships between academics and Chinese funding.

Attorney General William Barr gives the keynote address to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, CSIS China Initiative Conference, Feb. 6, 2020, in Washington.

Lieber is alleged to have participated in China's “Thousand Talents Plan,” a campaign to attract American and other specialists worldwide to accelerate its own academic, research and industry efforts.

U.S. colleges, universities, research labs, and industry partners are struggling with how to identify what they see as Chinese coercion and intellectual property theft. Lieber’s arrest is the latest in a string of academics charged with taking funding from Chinese interests or the Chinese government without disclosing it.

Mark Cohen, senior fellow at the University of California Berkeley Center for Law and Technology, told VOA that “this flurry of lawsuits and defunding and a re-examination of bilateral science cooperation … is significant.”

“It shows how pervasive” coercion and questionable funding has become.

Last year a University of Kansas researcher was charged with collecting federal grant money while working full time for a Chinese university.

A Chinese government employee was arrested in a visa fraud scheme that the Justice Department says was aimed at recruiting U.S. research talent.

A university professor in Texas was accused in a trade secret case involving circuit board technology.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced last year that it is investigating whether a dozen researchers there failed to report taking funding from foreign governments, specifically China.

The year before the agency sent a letter to more than 10,000 research institutions urging them to ensure that NIH grantees are properly reporting their foreign ties.

There are some “bad actors out there, but on the other hand, there is also a need for cooperation … a lot of scientists are being encouraged to develop collaborative relationships with Chinese entities,” Cohen said.

Most American scientists and researchers are used to an open environment, he said. Foreign students working on research “for the most part, they aren't working in universities on classified material.”

Cohen advocates stricter guidelines, which some universities have in place, while many do not.

“I think China does have a lot to account for, in this rash of cases, and of some of the other economic espionage cases of the past,” Cohen said. It would helpful too, he added, if China had its own guidelines “to ensure that they were not creating conflicts of interest.”

“We need collaboration. But we just need to do it the right way.”