As bombs tear apart the buildings and families within the decimated Syrian city of Aleppo following another broken cease-fire, a few hundred kilometers away in Lebanon, one refugee contemplated the idea of returning to Syria.

“At this point there is no chance of living there,” the 25-year old Mohamed,* who had been studying in Aleppo until 2014, told VOA.

“There are too many sides who want to kill me there. Not just me, but everyone, and it's something they can do easily.”

He is just one of the estimated 1.5 million Syrians who fled their country for Lebanon.

While many refugees do not expect to return for years, anticipating that the war will drag on, talk of sending Syrians back is becoming ever more common among some Lebanese politicians.

Non-integration

At this week’s Arab summit, Lebanon’s prime minister, Tammam Salam, reportedly called for the formation of an Arab committee to help the international community establish safe zones within Syria to host refugees.

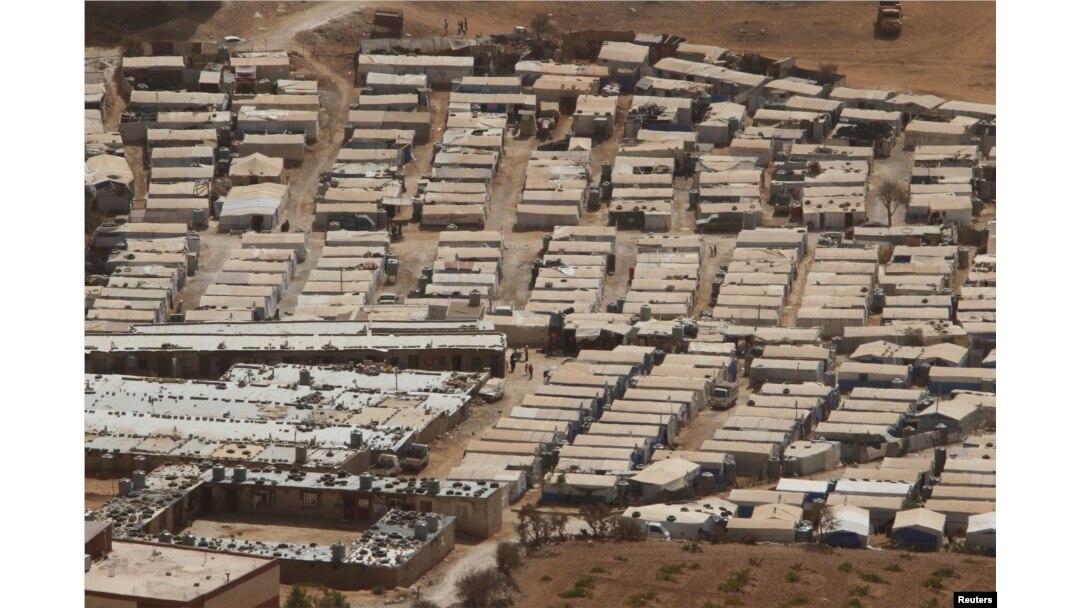

A general view shows tents of Syrian refugees on the outskirts of the Lebanese town of Arsal, near the border with Syria, Lebanon, Sept. 21, 2016.

This followed his speech last week at the first United Nations summit on refugees, where alongside appealing for more international aid, he was quoted as saying he would “not accept the integration of displaced people in Lebanon. The priority is to repatriate them.”

Salam, who qualified his speech afterward by stating that relocation would not be forced, reportedly gave the international community three months to begin putting the foundations in place for repatriation.

Meanwhile, Lebanon's labor minister, Sejaan Azzi, was more explicit in explaining his own plan.

Beginning this January, Azzi’s plan hinges on Russian-American cooperation in the creation of cease-fires and safe zones.

Troubling rhetoric

As with much else, the government is divided on the issue, but Bassam Khawaja, Human Rights Watch’s Lebanon researcher, is concerned.

“We’ve seen troubling rhetoric around the return of refugees to Syria for some time now, and it appears to have intensified,” he said.

Dismissing the short-term prospect of creating Azzi’s suggested safe zones, he said that “as a country at war, there are numerous risks of death, persecution and torture. It is not an environment to be returning refugees to.”

Although Lebanon was largely welcoming in the early years of the Syrian war, by January 2015 new visa rules restricted movement between the two countries, and refugees hoping for U.N. assistance must now sign a declaration that they will not work in the country.

Jordan and Turkey have been accused of carrying out forced repatriation, an act named refoulement and deemed illegal under international law.

In April, Amnesty International released a report saying that since January, Turkey had been rounding up groups of around 100 Syrians and sending them back home on an almost daily basis, criticizing the EU deal to send newly-arrived Syrians from Greece back to Turkey in the process.

In Lebanon, cases of refoulement have occurred, though on a more limited scale, and among Palestinian Syrians specifically.

In 2014, 40 Palestinian Syrians were sent back to Syria, and since then there have been fewer than five cases in which a forced repatriation was averted after an outcry.

This January, at least 200 Syrians stuck in Beirut’s Rafik Hariri Airport while on their way to Turkey were sent back to Syria.

The decision, prompted by new visa laws in Turkey, drew heavy criticism from human rights activists.

Responsibility for Lebanon’s desperate efforts to handle its refugee population partly lies with the international community and its failure to respond adequately.

Lisa Abou Khaled, a spokeswoman with the U.N. refugee agency in Lebanon, said a scheme to support the country had received $979m in international funding this year - less than half of what is required.

Praising the funding that had been received as "generous", she nonetheless said efforts to share the burden of refugees were “completely insufficient at this stage.”

FILE - Syrian women prepare food for their family outside their tents, at a Syrian refugee camp in the town of Bar Elias, in Lebanon's Bekaa Valley, March 29, 2016.

No time soon

Last year, the agency warned conditions for refugees in Syria’s neighboring countries were so bad some refugees were contemplating returning home, despite the danger.

HRW's Khawaja says there is “no indication that the refugees we’ve spoken to are open to returning to Syria in the conditions that currently exist,” he told VOA.

Now living in Beirut, like many of his countrymen, Mohamed dreams of returning to a peaceful homeland, but, with much of the country ablaze with war, and the Aleppo cease-fire in tatters, returning now is unthinkable.

Although the government is divided on the issue of repatriation, he is aware that politicians’ rhetoric can ramp up already inflamed feelings among some Lebanese.

“They always talk about us like we are a problem,” he said.

Only the war coming to an end could offer a feasible way of truly resolving the tensions within Lebanon over the refugee crisis, his housemate Khaled, who left Damascus in 2013, added.

“The Lebanese government knows there is a big problem, but they don’t have the answers and they cannot take us Syrians out [of the country].

“They are afraid. We are waiting, and we are afraid too.”

(The names of Khaled and Mohamed have been altered, or not been fully disclosed, to protect their identities.)