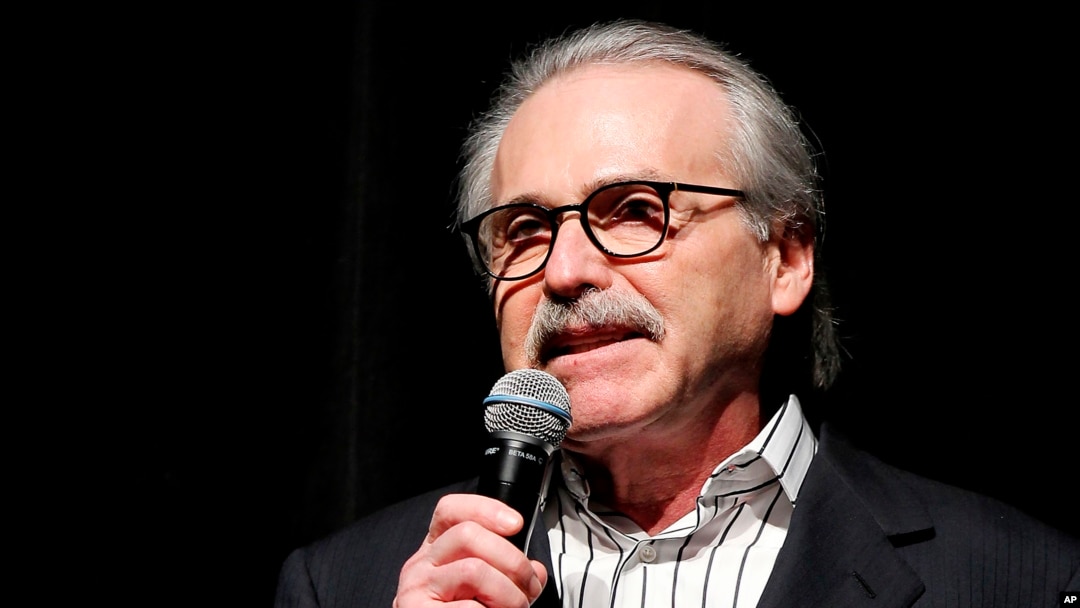

Former tabloid publisher David Pecker told a jury at Donald Trump’s criminal trial in New York on Tuesday that the future U.S. president summoned him to an August 2015 meeting to see how Pecker could “help the campaign.” That consequential discussion, Pecker said, led him to kill sex-related stories that would have hurt Trump’s 2016 run for the White House.

In one instance, Pecker told the 12 jurors that in a “catch and kill” scheme employed by his tabloid, National Enquirer, he killed a story about Dino Sajudin, a doorman at a Trump property in New York who claimed the real estate mogul had fathered an out-of-wedlock child.

Pecker testified he paid the doorman $30,000, even though upon further investigation his story turned out to be false.

Before the court session ended for the day, Pecker began testifying about a second instance that prosecutors say will be a saga of how he paid $150,000 for the rights to a claim by Karen McDougal, Playboy magazine’s 1998 Playmate of the Year, that she had a months-long affair with Trump, and then killed that story, too.

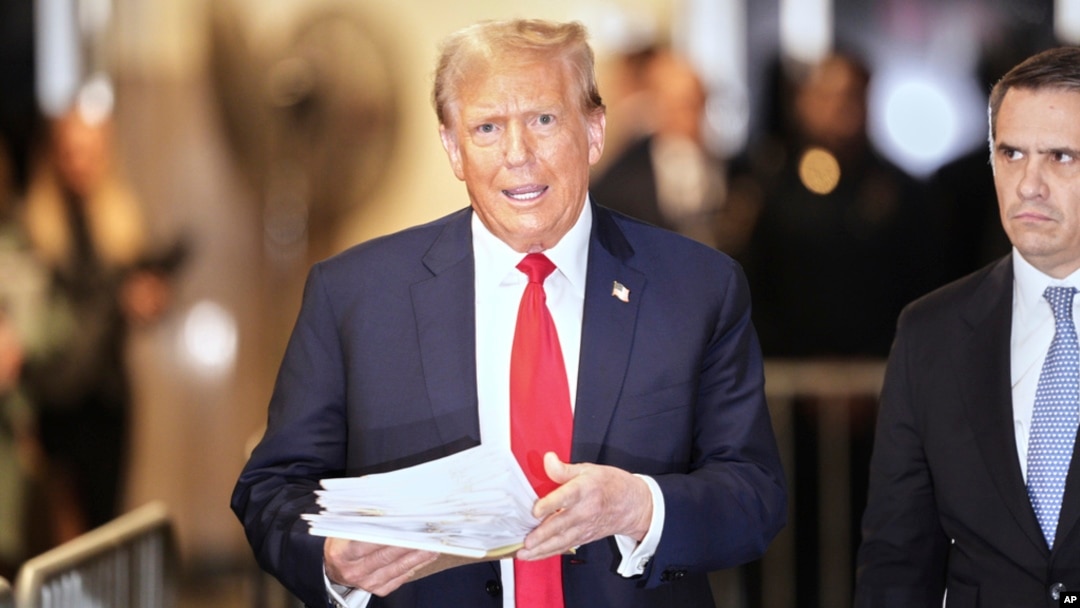

In the first-ever criminal trial of a former U.S. president, Trump is accused of scheming to hide hush money payments to Sajudin and two women, McDougal and porn actress Stormy Daniels, to keep the women from publicly talking about their alleged affairs with Trump just ahead of the 2016 election. Trump has denied their claims.

FILE - David Pecker, then-CEO of American Media, speaks at a Super Bowl party in New York, Jan. 31, 2014.

The 72-year-old Pecker said he had known Trump since the 1980s but at first didn’t know the purpose of the 2015 Trump Tower meeting in New York when Trump’s one-time lawyer and political fixer, Michael Cohen, called him and told him “the boss wanted to see me.”

Pecker said he was glad to help because “writing positive stories about Mr. Trump and covering the election and writing negative stories about his opponents” helped them both, boosting the grocery store tabloid’s sales while benefiting the Trump campaign. But he acknowledged to prosecutor Joshua Steinglass that killing stories that would have hurt Trump only helped the candidate, not the tabloid.

Pecker says the love child story would have been a major story at the time, but that he believed it was important to have it “removed from the market.” He said Cohen told him, “The boss would be very pleased.”

The jury was shown a contract the National Enquirer reached with Sajudin, the doorman, in which the words “Donald Trump’s illegitimate child” were featured prominently.

“I made the decision to buy the story because of the potential embarrassment it would have to the campaign and Mr. Trump,” Pecker said. In different ways, he said several times that he was acting on Trump’s behalf.

“If the story came back true, I would’ve published the story shortly after it was verified … after the election,” Pecker testified.

Pecker earlier had described Trump “as very detail-oriented, almost as a micromanager from what I saw. He looked at all of the aspects of whatever the issue was.”

Pecker said that at the first meeting with Trump and Cohen he asked that the “catch and kill” arrangement be kept secret, saying he wanted it “very confidential” because he did not want it known that he was helping Trump first to win the 2016 Republican presidential nomination and later defeat Democrat Hillary Clinton in that year’s national election.

Purchasing information to then kill a story is not normal practice in American journalism.

When McDougal started shopping her story shortly before the election, Pecker said he told Trump, “I think you should buy it.”

Pecker testified that Trump said he’d think about it and have Cohen call Pecker back.

Gag order

Before Pecker testified for the second day, and without the jury in the courtroom, New York Supreme Court Justice Juan Merchan held a hearing that turned contentious.

Another prosecutor, Christopher Conroy, argued that Trump should be held in contempt of court and fined for allegedly violating the judge’s gag order on 10 occasions by posting derogatory comments about prospective witnesses in the case on his Truth Social platform or on his official campaign website.

The gag order imposed on Trump bars him from attacking any of the witnesses, prosecutors, jurors, or court staff, and was later expanded to include some of their relatives. But the gag order still left Trump free to attack two key figures in the case, Merchan and the New York prosecutor who brought the case, Alvin Bragg.

Among other caustic comments, Trump characterized Cohen, a likely key prosecution witness, and Daniels as “sleazebags.”

Conroy contended that Trump “knows about the order, he knows what he’s not allowed to do, and he does it anyway. It’s willful."

Trump defense lawyer Todd Blanche said there was “no willful violation” of the gag order and said Trump’s attacks were political in nature, even if they were about witnesses in his criminal case.

Former President Donald Trump's attorney Todd Blanche listens as his client speaks to the media as they exit the courtroom following proceedings in his trial, at Manhattan Criminal Court in New York, April 19, 2024.

Merchan did not issue an immediate ruling on the contempt request but bluntly told Blanche, “You’re losing all credibility with the court.”

Afterward, while Merchan ordered a break in the proceedings, Trump complained about the gag order on Truth Social. In all caps, he accused Merchan of taking away his “right to free speech.”

“Everybody is allowed to talk and lie about me, but I am not allowed to defend myself,” Trump wrote. “This is a kangaroo court, and the judge should recuse himself.” Merchan has twice refused Blanche’s requests to recuse himself.

After court ended for the day, Trump told reporters, “I’d love to talk to you people, I’d love to say anything that’s on my mind, but I’m restricted.”

The case resumes on Thursday.

Charges explained

Trump is the country’s 45th president and the presumptive Republican presidential nominee in this November’s election. The New York case is one of an unprecedented four criminal indictments he is facing, encompassing 88 charges, all of which he has denied.

The hush money trial, however, could be the only one that occurs before the November 5 election in which he faces President Joe Biden, the Democrat who defeated him in the 2020 election.

Two of the other indictments — one state and one federal — accuse Trump of illegally trying to upend his 2020 loss, while the third alleges he illegally took hundreds of highly classified national security documents with him to his Florida estate when his presidential term ended, and then refused requests by investigators to return them.

No firm trial dates have been set in any of those three cases, and Trump has sought to push the start of those trials until after the November election.

Since Trump is required to be in court, the hush money case almost certainly will limit his time on the campaign trail as he runs against Biden.

He has denied the affairs and 34 counts of falsifying business records that, prosecutors say, show that he reimbursed Cohen $130,000. Cohen says he paid the money to Daniels to keep her quiet about her alleged one-night tryst with Trump in 2006.

Altering his company’s ledgers would be a misdemeanor offense, but to convict Trump of a more serious felony, prosecutors will have to convince jurors he committed an underlying crime, such as trying to influence the outcome of the 2016 election by keeping information about the alleged affairs from voters.

It is not illegal to pay hush money, and Trump may claim the payments were made simply to avoid disclosure of personally compromising moments of his life, not to try to influence the 2016 election.

The 12-member jury will have to agree unanimously on either a guilty verdict or acquittal. If the jurors fail to agree, there would be what is called a hung jury, leaving the prosecutors to decide whether to seek a new trial or drop the charges.

Each of the charges carries the possibility of a four-year prison term, although Trump is certain to appeal any guilty verdict and sentence.