We are approaching the 70th anniversary of the first performance by a venerable American musical ensemble, the gospel singing group known as The Blind Boys of Alabama.

Though he’s in his mid-80s now, Clarence Fountain, the last surviving, original member of the Blind Boys of Alabama, can still recall clearly the group’s first time singing in public.

“Way back in -- maybe [19] ‘45, [19]‘46 somewhere along in there - man in New York had a contest and what he did, he said, ‘We gonna have the Blind Boys from Alabama vs. the Blind Boys from Mississippi,” he said.

Fountain and his friends from the Alabama Institute for the Blind lost that contest. But they didn’t let it get them down. Instead he says,

“We hit the road," he said. "And we never looked back.”

The quartet singing tradition in America goes back to the 1890s. In the African-American community, quartets were based in the church, but you’d also find them in the barber shop and at work. In the case of the Blind Boys of Alabama, Fountain says their excitement about singing began when someone brought a radio into the Institute.

What they liked best was a gospel group called the Golden Gate Quartet.

“They harmonated, and they was speakin’ their words very clear,” Fountain said.

The Golden Gate Quartet was known for a specific type of gospel singing that had never been heard before, something that came to be called “Jubilee.”

“That’s how we learned how to sing," said Fountain. "Singin’ Jubilee -- let me explain it to you. It’s the same thing as rapping. What the rappers do now. The only thing is, when you sing Jubilee, you’re rapping in tune. You’re singing to the beat, but you’re rapping in tune.”

The Blind Boys were traveling and making a good living, singing like their idols throughout the 1940s. But after World War II, musical tastes changed.

“Rock 'n' roll came in in the early ‘50s, and it was a big thing,” Fountain said.

He says he saw plenty of people give up gospel singing for rock 'n' roll. People like Little Richard, Ray Charles and Sam Cooke.

“I was in the studio -- me and Sam Cooke -- when he changed from gospel and went over to rock 'n' roll,” Fountain said.

The musical styles of early rock 'n' roll and gospel were nearly the same. But the content… that was another story.

“We talkin’ ‘bout Jesus and they talkin’ ‘bout ‘my woman’ and ‘I love her’ and ‘she’s mine.’ You know all that whole mess," said Fountain. "There ain’t no difference in gospel or rock 'n' roll. I’ll give you an example, [he starts singing] ‘There’s a man, goin’ round takin’ names. I got a woman way over town, she’s good to me.'”

The Blind Boys knew they could make a whole lot more money if they gave up gospel for rock 'n' roll, but they decided against it.

“I made the Lord a promise and I talk to the Lord easily as I can talk to you,” Fountain said.

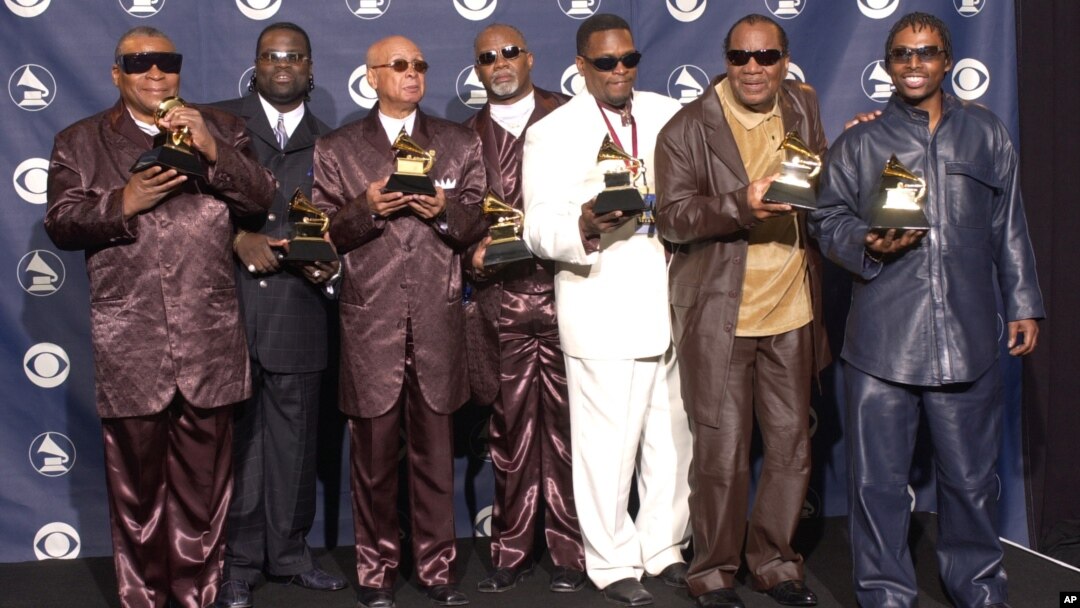

They stuck with it, they stayed on the road, and they kept on singing gospel. It was a risk, but five Grammy Awards and 70 years later, Fountain says it paid off.

“We just took a chance. And the Lord blessed us real good,” he said.

Though he’s in his mid-80s now, Clarence Fountain, the last surviving, original member of the Blind Boys of Alabama, can still recall clearly the group’s first time singing in public.

“Way back in -- maybe [19] ‘45, [19]‘46 somewhere along in there - man in New York had a contest and what he did, he said, ‘We gonna have the Blind Boys from Alabama vs. the Blind Boys from Mississippi,” he said.

Fountain and his friends from the Alabama Institute for the Blind lost that contest. But they didn’t let it get them down. Instead he says,

“We hit the road," he said. "And we never looked back.”

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5

Music of The Blind Boys of Alabama Nears 70th Anniversary

The quartet singing tradition in America goes back to the 1890s. In the African-American community, quartets were based in the church, but you’d also find them in the barber shop and at work. In the case of the Blind Boys of Alabama, Fountain says their excitement about singing began when someone brought a radio into the Institute.

FILE - Clarence Fountain smiles during an interview before the start of the band's show at the Fillmore in San Francisco, Jan. 11, 2002.

“And the thing we did -- we listened to music every day,” he said.What they liked best was a gospel group called the Golden Gate Quartet.

“They harmonated, and they was speakin’ their words very clear,” Fountain said.

The Golden Gate Quartet was known for a specific type of gospel singing that had never been heard before, something that came to be called “Jubilee.”

“That’s how we learned how to sing," said Fountain. "Singin’ Jubilee -- let me explain it to you. It’s the same thing as rapping. What the rappers do now. The only thing is, when you sing Jubilee, you’re rapping in tune. You’re singing to the beat, but you’re rapping in tune.”

The Blind Boys were traveling and making a good living, singing like their idols throughout the 1940s. But after World War II, musical tastes changed.

“Rock 'n' roll came in in the early ‘50s, and it was a big thing,” Fountain said.

He says he saw plenty of people give up gospel singing for rock 'n' roll. People like Little Richard, Ray Charles and Sam Cooke.

“I was in the studio -- me and Sam Cooke -- when he changed from gospel and went over to rock 'n' roll,” Fountain said.

The musical styles of early rock 'n' roll and gospel were nearly the same. But the content… that was another story.

“We talkin’ ‘bout Jesus and they talkin’ ‘bout ‘my woman’ and ‘I love her’ and ‘she’s mine.’ You know all that whole mess," said Fountain. "There ain’t no difference in gospel or rock 'n' roll. I’ll give you an example, [he starts singing] ‘There’s a man, goin’ round takin’ names. I got a woman way over town, she’s good to me.'”

The Blind Boys knew they could make a whole lot more money if they gave up gospel for rock 'n' roll, but they decided against it.

“I made the Lord a promise and I talk to the Lord easily as I can talk to you,” Fountain said.

They stuck with it, they stayed on the road, and they kept on singing gospel. It was a risk, but five Grammy Awards and 70 years later, Fountain says it paid off.

“We just took a chance. And the Lord blessed us real good,” he said.