Fifty-seven years ago, Martin Luther King Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led a March on Washington to bring attention to Black Americans' racial and civic inequality in society.

A few weeks ago, in late August, a racially diverse crowd also marched through Washington with the hope of rekindling the spirit of the 1963 march.

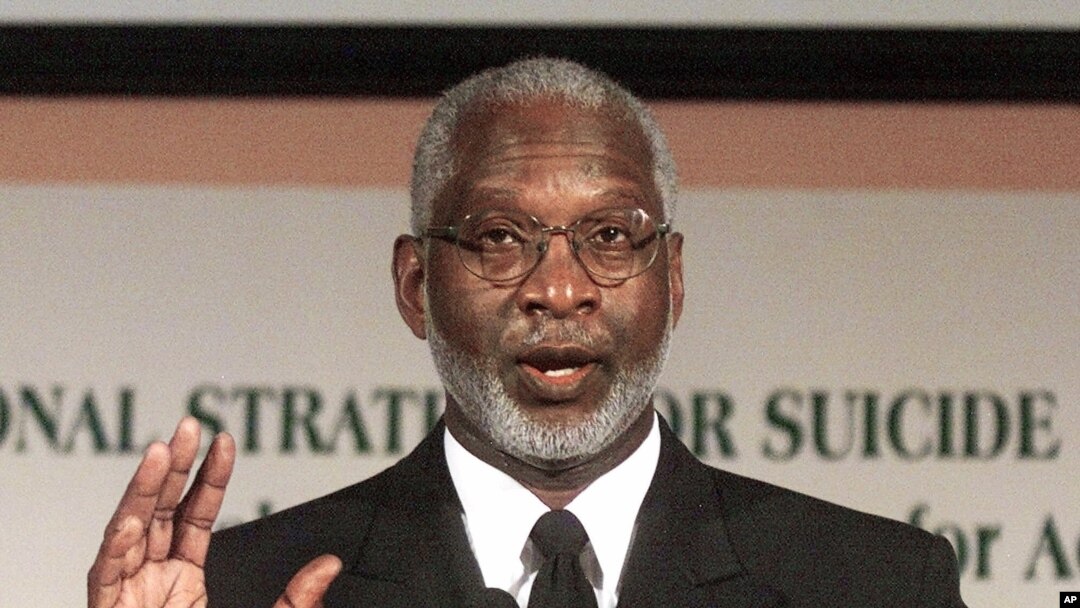

Like King, Dr. David Satcher has devoted his life to civil rights, with one difference — Satcher has pushed to ensure that African Americans and other minorities have the same access to health care as their white counterparts.

Satcher was born in poverty in what is called "the deep South" — cotton-producing states that depended on enslaved labor before the U.S. Civil War in the mid-1800s. Even after the war and emancipation, Black Americans were subjected to harsh discrimination throughout the U.S., but especially in the South.

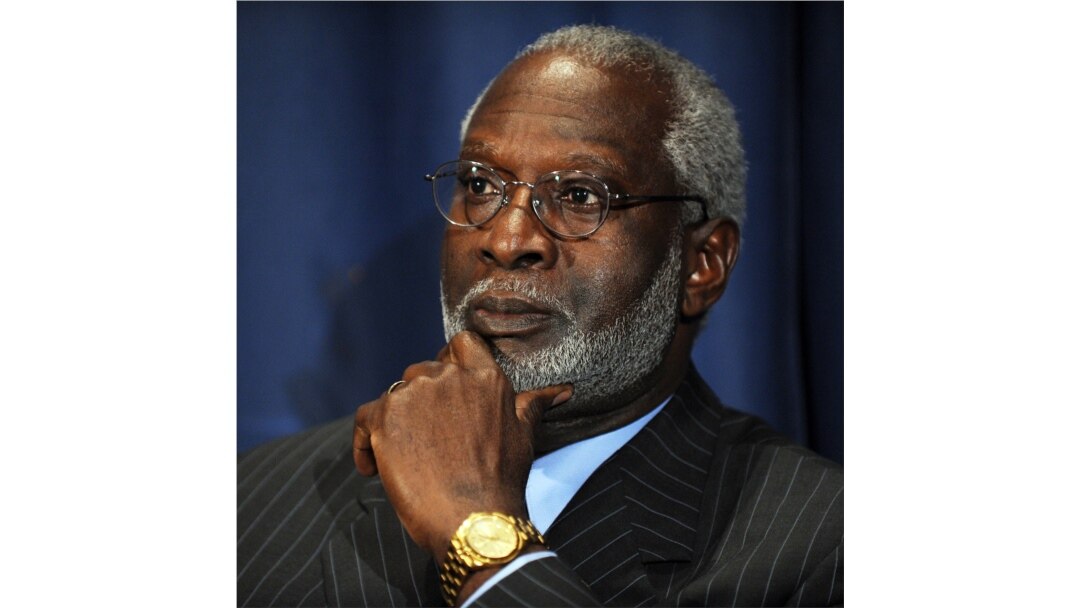

Former Surgeon General David Satcher participates in a press conference titled a "National Call to action on Cancer Prevention and Survivorship" on July 23, 2008 at the National Press Club in Washington.

Despite these obstacles, Satcher became a physician and a public health administrator. He was a four-star admiral in the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. He was a U.S. Surgeon General and simultaneously, assistant secretary of health. Later, he became director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Illness led to career in medicine

The inspiration for his life's work started in childhood when he became gravely ill.

"I was just 2 years of age when I developed whooping cough and pneumonia," he said.

Satcher was born in 1941. Until 1965, segregated hospitals in the South did not admit Black patients, he said. That year, two health care programs — Medicaid and Medicare — were enacted into law. Medicaid is a health insurance program for the poor. Medicare does the same for the elderly. Hospitals in the South decided to admit Black patients to receive funds from these programs.

"And it was only the dread of not allowing hospitals to be on Medicaid and Medicare — that was what led hospitals to desegregate and to say they were going to stop,” he said.

Until that time, Satcher said most Black children with a serious illness died at home. He said his parents had already buried two children and did not want to bury a third when he became ill.

Picture of David Satcher as a child picking cotton with his father, Wilmer, and older brother on the family farm. (Photo courtesy of Satcher family)

The Satchers lived on a small farm in Alabama, about an hour away from the nearest town. His father convinced the only Black doctor in the area to make a house call on his day off.

"He was a busy doctor, and he came out to see me and spent most of the day," Satcher said. “And when he left, he told my parents he didn't expect me to live out the week. But he also took the time to tell them what to do to give me the best chance to survive."

Satcher said he grew up hearing that story. By the time he was 6, he wanted to become a doctor. Even though he could not have realized it at the time, his illness was an introduction to segregation and health disparities that still exist between African Americans and white people.

Dr. David Satcher and his siblings getting a checkup from a Black doctor. At the time, Black doctors did not have admitting rights to hospitals in the South.(Photo courtesy of Satcher family)

"The majority of African Americans don't have a primary care doctor," Satcher said.

This means that health problems are often not detected before they cause a stroke, a heart attack or another grave illness.

Satcher wanted to meet Dr. Fred Jackson, the man he credits with saving his life. But Jackson died at an early age from a stroke before Satcher turned 5.

‘Social determinants of health’

African Americans have disproportionately higher rates of heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, HIV — diseases known to shorten lives, according to the CDC. Statistics from U.S. health agencies also show that Black people also disproportionately die of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

Satcher said their poorer health is largely due to what he calls "social determinants of health."

"Poverty is, in and of itself, part of our health legacy and problems," he said.

Data from the U.S Census Bureau show that twice as many African Americans live in poverty than white Americans. Medicaid is designed to overcome some of these disparities, but the disparities still exist.

In April, the American Association of Endodontists, dentists who specialize in saving teeth, sent a letter to governors and state health departments urging officials to recognize endodontists as essential emergency health care providers.

In their letter, the group pointed to the story of Diamonte Driver, a 12-year-old African American boy who died when bacteria from an abscessed tooth infected his brain. A routine dental visit and an $80 tooth extraction would have saved his life.

His mother worked at low-paying jobs and could not afford the fee, nor could she find a dentist who would treat him. When Diamonte became seriously ill, his mother took him to the hospital, but it was too late. After two operations and more than six weeks of hospital care, he died Feb. 27, 2007.

Dr. David Satcher during his college years. (Photo courtesy of Satcher family)

Satcher said the difficulty Diamonte and his mother faced 13 years ago still happens today. At the time, Sally Cram, a practicing periodontist in the Washington, D.C., area, told ABC News, "Unfortunately, this is more common than we'd like it to be." Cram said what Medicaid reimburses a dentist does not cover the cost of the treatment.

Additionally, Cram reported, even medical professionals have difficulty finding dentists who accept Medicaid. The state of Maryland, where Diamonte lived, has improved dental service for poor children, but finding a doctor who takes Medicaid is still a problem for many poor people.

A study by the University of Minnesota looked at various specialties. It found that doctors who accept Medicaid vary by specialty. For example, the study showed that 30% of general practitioners do not accept Medicaid patients, while 65% of psychiatrists do not take it.

Another factor that prevents access to health care and a healthy lifestyle is that many African Americans have lower-paying jobs and higher unemployment, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

African Americans often do not have access to nutritious food. "Junk food," such as potato chips and french fries that are salty and full of fat, is cheaper than fresh fruits and vegetables.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture reports that low-income communities are more likely to lack stores that sell healthy and affordable food. Instead, the food stores in these communities tend to sell processed foods that are high in sugar and fats. The Agriculture Department reports that this situation "may contribute to poor diet, obesity, and other diet-related illness."

In addition, many African Americans and other minority groups live in neighborhoods that are not safe. The Department of Housing and Urban Development reports that "low-income people and racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected" by violent crime.

Satcher said these factors affect the health of minorities.

"And so, how we eat, the extent to which we have safe places to be physically active, and the extent to which we have regular physical activity — that's one reason schools are so important. Because (if) many of our children (did not go) to school, they wouldn't be getting a nutritious diet, and they wouldn't have safe places to be physically active,” Satcher said. “So, all of those things come into what we call the 'social determinants of health.’”

Satcher has retired from public service, but he still teaches at Morehouse School of Medicine, where he founded the Satcher Health Leadership Institute. He still works actively to promote health care equality in presentations at medical schools and colleges, and in his latest book, "My Quest for Health Equity: Notes on Learning While Leading (Health Equity in America)."