The commander of the National Guard in Washington told Congress Wednesday it took more than three hours to get approval to deploy troops to the U.S. Capitol on January 6 to confront rioters who were storming the building trying to block lawmakers from certifying Democrat Joe Biden as the country’s new president.

Maj. Gen. William Walker, chief of the District of Columbia National Guard, told two Senate committees investigating the deadly mayhem that he did not get Defense Department approval to dispatch hundreds of troops until after 5 p.m. — more than three hours after then-Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund had frantically told him that a mob had breached the building.

Walker said the delay appeared to be the result of a cumbersome troop approval process and possibly a reluctance by some officials to approve a public show of force at the U.S. symbol of democracy. In the meantime, the rioters overwhelmed authorities and barged into the U.S. seat of legislative government, ransacked congressional offices and scuffled with police, leaving five people dead.

Walker said that in previous instances of civil disorder during his 19 years commanding National Guard troops in Washington — including racial justice demonstrations last spring in Washington — permission to deploy troops to quell unrest had been granted immediately.

He said he could have dispatched 155 troops at 2 p.m. shortly after the first rioters rampaged into the Capitol, where the victims included a Capitol Police officer whom authorities believe was fatally doused with bear spray.

Those 155 officers “could have made a difference,” Walker told a hearing held jointly by the Senate Homeland Security and Rules committees. “We could have pushed back the crowd.”

Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar pointed out that millions of people across the country were watching the riot on live television even as the troop deployment languished.

Even after the Defense Department approved the deployment of the National Guard troops at 4:32 p.m., it took another 36 minutes before Walker was told he could send in his troops who were waiting in buses for the short drive to the Capitol.

“I was frustrated … stunned” by the delay, Walker testified. “I would have sent them immediately.”

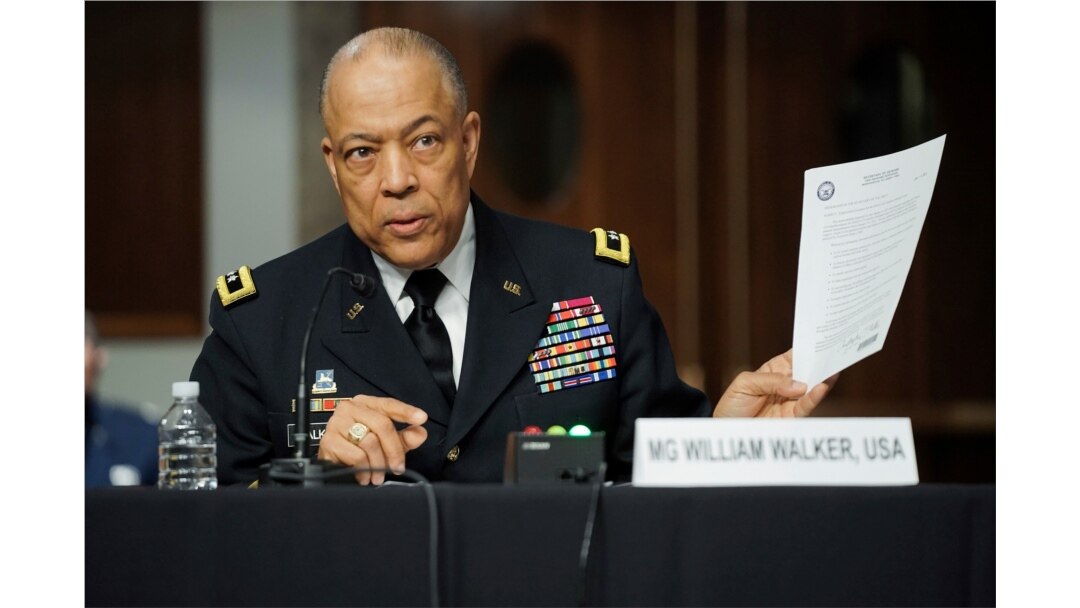

Army Maj. Gen. William Walker, Commanding General of the District of Columbia National Guard, answers questions during a hearing, March 3, 2021, to discuss the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Republican Sen. Rob Portman said, “That can’t happen again,” a sentiment with which Walker agreed.

Eventually, law enforcement officials restored order at the Capitol. In the early hours of January 7, lawmakers certified the results of the Electoral College and Biden’s victory. He was inaugurated as the country’s 46th president on January 20.

While lawmakers investigate the circumstances surrounding the January 6 attack, Capitol Police said they are aware of intelligence claims of a possible militia group plot to attack the Capitol again on Thursday, March 4, the date when some right-wing conspiracy groups believe Trump will be sworn in as president.

Until 1933, March 4 was the date when U.S. presidential inaugurations were held.

Several hearings planned

Wednesday’s hearing is one of several that Congress is holding to investigate how the storming of the Capitol unfolded after former President Donald Trump urged hundreds of his followers at a rally near the White House to “fight like hell” in confronting lawmakers to try to upend the election results.

On Tuesday, FBI Director Christopher Wray defended the bureau against criticism that it missed warning signs about the assault and failed to adequately sound the alarm about the possibility of violence by Trump supporters.

At the same time, Wray, in his first congressional appearance since the riot, disputed assertions promoted by some on the right that far-left activists masquerading as Trump supporters were involved in the deadly attack.

More than 100 police officers were injured. A nationwide manhunt in the aftermath of the insurrection has led to the arrest of more than 300 rioters, including 33 members of anti-government militias and other far-right groups.

Testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Wray said the FBI took multiple steps to ensure a “raw” intelligence report warning about the possibility of a violent attack on the Capitol reached key law enforcement agencies the day before.

The January 5 report, prepared by the FBI’s Norfolk, Virginia, field office, cited online extremist chatter about the possibility of violence and “war.”

The FBI typically verifies such raw information before sharing it with law enforcement agencies. But in this case, the threat was concerning and “specific enough” that the FBI decided to share it with the Capitol Police, the Washington city police and other law enforcement agencies as soon as possible, Wray said.

Yet the report was not flagged for top officials responsible for securing the Capitol, those officials testified last week, raising questions about a breakdown in intelligence- sharing.