For formerly jailed investigative journalist Natalia Radina, Tuesday's shock acquittal of Russian reporter Ivan Golunov is a small but significant victory in a much larger war to defend press freedoms across the post-Soviet sphere.

"Thank God, Ivan is freed," said Radina, top editor of Charter 97, an independent investigative news outlet that covers governance and corporate corruption in her native Belarus.

"This became possible only thanks to the solidarity of journalists in Russia and all over the world," she said. "This is a good example of how we should protect victims of political repression: we should protest immediately and en masse. I look on Russians with admiring envy."

Golunov, a 36-year-old reporter with the Riga-based independent media outlet Meduza, was detained Thursday on charges that supporters said were trumped up to punish him for his investigative reports on Moscow city officials.

Golunov, who had been charged with attempting to deal a "large amount" of drugs, said he was beaten in detention. His lawyers insisted drugs had been planted on him, and police later admitted that photographs of a drug lab found at a crime scene were not taken at Golunov's flat.

In an unprecedented gesture of solidarity, on Monday Russia's three major business newspapers, Kommersant, Vedomosti, and RBK, published identical front pages with the headline "We Are Ivan Golunov" in large type, along with a cautiously worded statement saying they couldn't "rule out" the possibility that Golunov's charges were filed in retaliation for his reporting.

According to Bloomberg columnist Leonid Bershidsky, Golunov's one-time editor, Monday's trio of matching headlines was the culmination of a subtle but protracted protest throughout the Russian mediasphere.

"Many news outlets effectively boycotted coverage of the St. Petersburg Economic Forum, traditionally Putin’s favorite international event of the year," Bershidsky wrote.

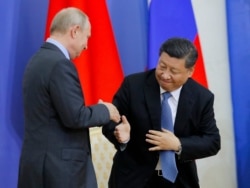

"The event was meant to be a demonstration of Putin’s close friendship with Chinese President Xi Jinping ... [but] Golunov beat Putin in both social media and traditional media mentions," he reported. "Journalists stood in a disciplined line in front of Moscow’s police headquarters, waiting their turn to hold a sign demanding his freedom."

Russian law bars unsanctioned rallies, but one-person pickets don't require permission from state officials.

"This is victory ... I'm crying," tweeted Meduza editor-in-chief Ivan Kolpakov on Tuesday, while opposition leader Alexei Navalny called it "an inspiring and motivating example of what simple solidarity ... can achieve."

A common tactic

To Radina, however, Golunov's acquittal was only an aberration in an otherwise tragically commonplace trend for journalists — and sometimes rights activists — across the region.

Chechen journalist Zhalaudi Geriyev recently completed a three-year jail sentence on what was widely panned as a politically motivated drug charge, while Nikolai Yarst, now a VOA reporter, had an illicit substance planted in his vehicle in Sochi shortly before the 2014 Winter Olympics.

Chechen human rights advocate Oyub Titiev, who was given a four-year penal colony sentence in March on drug charges, was granted early release by a Russian court on Monday.

Igor Rudnikov, editor of Novye Kolesa, the leading independent paper is Russia’s western exclave of Kaliningrad, is currently facing up to 15 years in prison on charges of trying to extort money from a senior Kaliningrad police officer who had been a target of his investigative reporting.

Strength in numbers

"Support for all independent media, it has decreased significantly [across the region]," said Radina, who herself was jailed in 2011 for reporting on corruption in Minsk before being pressured to leave the country. She ultimately claimed asylum in neighboring Lithuania.

In 2010, plainclothes officers charged into her newsroom on the eve of Belarusian presidential elections, beating some reporters and confiscating all the equipment.

"The interrogations lasted for four to five hours, and mostly the police officers weren't interested in our reporting, but how Charter 97 worked," she said. "From where did we receive funding, specifically where in the West? It was quite obvious that the task was to destroy an independent resource and cut off from any sources of funding."

Just months prior to the raid, Charter 97's founding editor, Oleg Bebenin, a young married father of two, was found hanged in the stairwell of his weekend home outside Minsk. No suicide note was found, and friends and family members who saw the body described bruising and a badly twisted ankle.

Although Charter 97's web site remains blocked by Belarusian officials, the site remains accessible outside the country, and has even expanded its audience by conducting investigative reporting in the Baltics, Poland and various post-Soviet republics.

"We also have quite a lot of readers from Ukraine and Russia, as we today cover problems and situations not only in Belarus, but also among our neighbors," she said, explaining that staff members have also acted as surrogate investigators "in solidarity" with colleagues in Armenia and Kazakhstan.

"In general we are all in the same boat," she said, adding that safeguarding press rights in one country enables it to be a resource in neighboring regions. "We have a very similar situation in these post-Soviet regimes."

The international media watchdog Reporters Without Borders hailed Golunov's release as the result of a "historic mobilization of Russian civil society."

"Now those who tried to set him up must be judged," the NGO wrote on Twitter.

"Russian officials tried to frame Ivan Golunov," Alexey Kovalev, Golunov's editor, wrote in The Guardian, "but instead made him a hero."

This story originated in VOA's Russian Service [ http://www.golos-ameriki.ru/ ]. Some reporting is from AFP.