In July 2013, Sana Mustafa was sitting in a classroom in the U.S. state of Rhode Island when she received a message on Facebook from her sister in Syria.

“They took our father, and we’re leaving the country,” her sister informed her.

Mustafa, now 29, was attending a six-week summer school in the United States. The rest of her family was living in Damascus, the Syrian capital.

“My mother wasn’t home when my father was taken,” she told VOA. “Our neighbors told my mother that the Shabiha came and took her husband.”

The Shabiha, a term used by Syrians for government-sponsored militias, have been accused of major atrocities against anti-government activists since the beginning of Syria’s conflict in 2011.

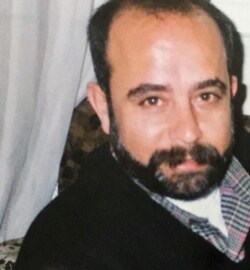

Since being taken from his Damascus apartment, the whereabouts of Mustafa’s father, Ali, have been unknown.

“The apartment is located in a regime-held area, not far from the presidential palace, so it’s very obvious and clear that it was the Syrian regime that took my father,” Mustafa said.

She said her family “tried everything to get any piece of information about my father … even bribing some regime officials. But no one gave us answers.”

After leaving Syria, Mustafa’s mother and younger sister settled in Canada. Her other sister now lives in Germany.

Thousands of cases

Ali Mustafa is one of tens of thousands of people who have disappeared since the beginning of the war.

While the exact number of missing persons cannot be determined, human rights groups say all parties involved in the conflict are responsible for the disappearance of nearly 100,000 people.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights estimated in a report in August 2020 that forces loyal to the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad alone were responsible for nearly 85,000 missing people.

Rights experts say the fact that Syrian prisons and other detention facilities are off limits to outsiders makes it nearly impossible to determine the number of disappeared Syrians.

“There’s just so many people that are missing, and we have no idea as to their whereabouts,” said Philippe Nassif, Middle East and North Africa advocacy director at Amnesty International.

“We can assume a large number of them were killed in Syrian prisons, but we are not entirely sure exactly just how many that actually amounts to or what percentage of those who are missing that we can confirm have been deceased, likely deceased or still being held against their will in captivity,” he told VOA.

Multiple actors

While Nassif agreed that most of the missing people disappeared under the Syrian government’s security forces, he said rebel and extremist groups such as Islamic State (IS) also have been responsible for many enforced disappearances in the war-torn country.

Nearly four months before the city of Raqqa was captured from IS militants by U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces in October 2017, Um Hashim, a Raqqa resident, said two of her sons were taken by the militant group.

“I didn’t know where they took them and couldn’t even ask a question about them,” the 57-year-old woman said. “It was a chaotic time, and we had to leave Raqqa for a displacement camp, as the [Syrian] Democratic Forces were coming closer.”

Two months after the liberation of Raqqa, Um Hashim returned to search for her sons, both in their 20s.

“I went everywhere to ask about them,” she told VOA. “The new authorities said they had searched all prisons that belonged to (IS) and found no trace of them.”

Despite her sons’ abduction four years ago, Um Hashim believes “they are still alive somewhere out there.”

Rights groups say that in addition to the missing Syrians, more than 2,000 Yazidis, mostly women and children who were taken by IS as sex slaves, are still missing.

Accountability

Experts say local and international rights groups must be prepared for the time when those responsible for enforced disappearances and other abuses are held accountable.

“The most important thing that could be done now is the documentation of all cases of disappearances throughout the country,” said Bassam Alahmad, executive director of Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ), an advocacy group that documents human rights abuses in Syria.

“Whether it’s in Ras al-Ayn, Tel Abyad or Afrin (three towns controlled by Turkish-backed armed groups), or in any other city in Syria, more efforts should be dedicated by rights groups for documentation that could be used as evidence against the perpetrators in the future,” he told VOA.

Alahmad said the STJ has been working with its partners to document violations, including enforced disappearances, perpetrated by all actors in Syria’s conflict.

Nassif of Amnesty said his organization’s position on the disappearance file in Syria is the establishment of “an international tribunal for those responsible for these atrocities.”

And for that, international human rights bodies “need to investigate to find out the names of all of these people and whether there is a place where all their names have been listed, the condition where they were held, even if they are deceased. And where they were held, how they were killed. Was it starvation? Was it execution?” he said.

“All these kinds of things we need to have documented and put out in the public, or at least in the court system first, so the appropriate decisions can be made as to who’s responsible and their punishment,” Nassif added.

For Sana Mustafa, who has been advocating for her father’s case and other disappeared Syrians, seeking justice is no longer a personal cause.

“This issue is not only a humanitarian one but also a political one,” she said. “It’s a living proof of war crimes committed by the Syrian regime and other groups.”