The children — 10 in all — were in the yard that morning at 7 a.m., having just returned from early morning religion classes.

When a mortar struck nearby, they huddled together asking each other, “Where did it come from? Where did it hit?” Minutes later, another mortar crashed to the ground about 5 meters from the children.

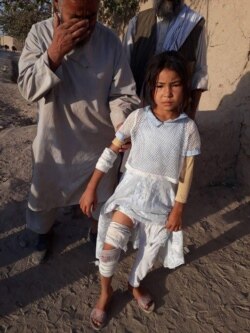

Tamana, 10, and her brother, Peermohammad, 13, died in the blast. Nine-year-old Fazel Ahmed’s arm was severed. Shrapnel pierced the leg of his sister, Masuda.

“I ran outside and saw smoke and dust,” said Nasrin Ozbek, the children’s mother. “I could smell the flesh.”

It happened over a year ago, but it did not drive the surviving eight children and their parents from Afghanistan. It was not until the United States announced its imminent departure that they decided they had to go.

A 19-year-old man in the family worked for the Afghan National Army, and the Taliban was targeting soldiers, even before they took over the region.

Now controlling the country, the Taliban say they will not carry out “revenge killings,” but refugees in Turkey say the statements are hard to believe. In the months leading up to the fall of Kabul, Taliban fighters targeted and killed government workers and soldiers, refugees say, and in some places, demanded forced marriages of women and girls.

“The Taliban were coming to occupy my village,” said Abdul Kareem Ozbek, 40, the children’s father. “We left just before they arrived.”

'More brutal'

The current relative calm in Afghanistan’s capital, Kabul, has been accompanied by official Taliban statements offering amnesty for former Afghan soldiers and security forces, and insisting that women and girls will be allowed to attend school and work.

“But with Islamic hijab,” one commander told CNN on the streets of Kabul. To clarify, he didn’t mean ordinary Muslim headscarves but fully covered faces.

In a small apartment in Van, a city near the Turkish border with Iran, refugees from Kabul say they believe the Taliban may have moderated some of their policies, but they will eventually prove themselves to be “more brutal” than the previous generation of fighters.

Nafisa Alwozai, a 40-year-old mother, came of age in a village outside of the city in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. She was forced to quit school and stay home, eventually marrying a man heavily bearded, in accordance with Taliban regulations.

“Back then, people welcomed them at first,” she said. “But eventually they showed us who they really were.”

Three months ago, she added, it became apparent to her that the Taliban were returning to power after U.S. President Joe Biden announced a complete troop withdrawal by September 11, 2021. She said her husband was killed by Taliban fighters 10 years ago, and he was a police officer, making their five sons potential targets.

Women and girls also face different dangers now than they did from the Taliban of the 1990s, added Abdul Shahagha, 30, Alwozai’s brother-in-law.

“Now, they are looking for girls who are 16 or 17 years old to marry,” he said.

He went on to describe the marriages not as romances but as abductions. “Before, they didn’t do such things,” he said.

Pressure to switch sides

Among the refugees in Van, many former Afghan soldiers and police officers say they may have been able to survive at home if they had agreed to join the Taliban.

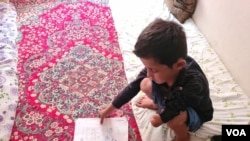

In a crowded, bare apartment, Omid Suleyman Zada, 26, said he left Kabul a month ago after receiving death threats via mobile phone from Taliban fighters.

“They kept calling and saying, ‘You have to leave the government forces and come with us,’” he said, his small son peeking his head out from behind his father.

Three months ago, the Taliban killed his brother, Zada added, breaking down in tears.

After receiving the last threat, the family decided to flee the country. They gathered $1,000 per person — the bare minimum that smugglers charged to get out of Kabul to Van. Now, with the Taliban in charge of the borders, it is not clear how refugees will get out of the country, or how much it will cost.

“It is my homeland,” Zada said. “I never went out of the country before now. But I had to leave.”

Ozbek, the father of eight surviving children, also felt he had no choice but to flee, even knowing how dangerous the road to Turkey could be. Along the way, smugglers in Turkey kidnapped him and his family for 47 days, and he endured several arrests and torture.

“Look here,” he said, pointing to angry red scars inside his elbows. “(Turkish) security forces dug wirecutters into my arm and told me, ‘Do you want to come to Turkey now?’”

Last week, only two days before the fall of Kabul, Ozbek received a picture by text of a friend who had worked for the Afghan military. His friend and about 30 other soldiers had been executed by the Taliban, the message said, according to Ozbek.

He then lowered his voice and switched to halting Turkish, a language his wife and children do not understand.

“My brother’s son was also killed,” he said. “But I haven’t told them, yet.”

Mohammad Mahdi Sultani contributed to this report.