Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan recently directed authorities to release hundreds of female prisoners who are awaiting trial for minor offenses or who have served most of their prison terms.

Rights advocates have hailed the move, hoping it will help ease the plight of the country’s female prison population.

Khan’s directive last week stemmed from a new, official study that found women’s jails are rife with poor conditions and that authorities often ignore laws meant to protect female inmates.

The report by the federal Human Rights Ministry said that of the 1,121 women in prison as of mid-2020, nearly 67% had not been convicted of any offense and were detained while awaiting conclusion of their trial.

The government has pledged to pay the financial penalties outstanding against female prisoners whose remaining sentences are less than three years so they could be released immediately.

Khan has also asked for “immediate reports on foreign women prisoners and women on death row for humanitarian consideration” and possible release.

“Inmates of jails in Pakistan do not often have a reason to collectively rejoice, but a humane decision by the federal government will have many female prisoners doing precisely that,” the English-language daily DAWN wrote in its editorial on Khan’s announcement.

Need for reform

On Monday, Human Rights Watch (HRW), responding to the official actions, noted that the ministry’s report had highlighted “the massive scale of mistreatment” of women prisoners in Pakistan and the need for broad and sustained prison reform.

“While an important step, this report can only bring change if Pakistani authorities follow its recommendations and end widespread abuse,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at the global organization.

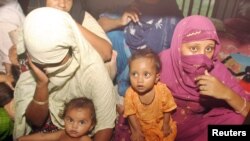

The official report has found that 134 women had children with them in prison, some as old as 9 and 10, despite the legal limit of 5 years.

“A critical lack of funding in the prison health care system has meant that mothers whose children are with them in prison often lack essential health care, leaving both the women and the children at risk of contracting infections,” HRW said.

The outbreak of the coronavirus in Pakistan prompted the Supreme Court in April to warn authorities that inmates in the country’s overcrowded prisons could become victims of the pandemic.

The court ordered Khan's government to reduce prison congestion by freeing prisoners suffering from a mental or physical illness, inmates 55 years or older, male prisoners without any past convictions who are awaiting trial, as well as women and juvenile inmates.

Overcrowding

Pakistan’s overall prison population officially stands at more than 73,000 inmates, with most of them living in cramped conditions. Government estimates put the total capacity of prisons across the country at nearly 58,000.

Most of the detainees are said to be awaiting trial and have not been convicted. Critics say court cases in Pakistan can take years, if not decades, to conclude, even ordinary disputes, because of a shortage of judges and lawyers, and rampant corruption, particularly in the lower judiciary.

A government study released earlier this year had also highlighted widespread problems in Pakistani prisons. It found that almost 2,400 prisoners at the time suffered from chronic contagious diseases such as HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis.

“The Human Rights Ministry report is an opportunity for the Pakistan government to take meaningful steps to improve the treatment of women in prisons in the country and start a much-needed process of systemic, large-scale prison reform,” Adams said.