A Guatemalan judge ordered prominent journalist Jose Ruben Zamora back to prison this week in a move that the leader of his legal team called “inhumane.”

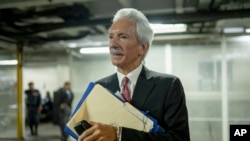

Zamora on Monday returned to Mariscal Zavala prison in Guatemala City on the orders of Judge Erick Garcia, whose decision came after another court revoked house arrest from the elPeriodico founder.

The publisher is awaiting another trial in a money-laundering case that press freedom groups say is politically motivated.

“We’re very troubled by what’s happening in Jose Ruben Zamora’s case, because what we’re seeing here is a total breakdown of rule of law in Guatemala,” Caoilfhionn Gallagher, who is leading Zamora’s international legal team, told VOA.

“He obviously shouldn’t have spent a single day in prison. This latest revocation of his house arrest terms is legally problematic, grossly unfair and inhumane,” Gallagher added.

Zamora, 67, attended the hearing on Monday. Near the end of his appearance, he called the ruling “arbitrary.”

During the hearing, the judge said he and his staff had been threatened by unnamed individuals, but he did not elaborate.

“They left him cornered with no way out,” Zamora said in court.

Zamora founded elPeriodico in 1996. The newspaper was known for its investigations into corruption across multiple governments in Guatemala.

But in 2022, authorities arrested Zamora and later froze the newspaper’s assets. The publication was forced to shutter in 2023.

A court later sentenced Zamora to six years in prison on money-laundering charges. An appeals court overturned the conviction and ordered a new trial for 2025.

Zamora’s legal team has rejected all the accusations. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has also determined that Zamora’s detention is arbitrary and called for his release.

The publisher spent more than 800 days in prison before a court in October granted him house arrest while he awaited his new trial. Another court in November revoked Zamora’s house arrest, but his lawyers were able to postpone the order for a few months.

Artur Romeu, director of the Latin America bureau of Reporters Without Borders, called the decision to reimprison Zamora a “blatant case of judicial weaponization.”

In response to a request for comment, Guatemala’s Washington embassy directed VOA to comments made earlier this week by Guatemalan President Bernardo Arevalo about Zamora.

“This is an absolutely baseless case that exposes the worst of the crisis in our judicial system and highlights the criminalization strategies being implemented by the Public Ministry,” Arevalo said Monday.

The Public Ministry is Guatemala’s Justice Ministry. It is led by Attorney General Maria Consuelo Porras, who was sanctioned by the European Union in 2024 for “undermining democracy,” including by targeting journalists and trying to prevent Arevalo from assuming office.

During Zamora’s previous time in prison, the publisher was subjected to conditions that Gallagher characterized as “inhumane and degrading” and “a violation of international standards.”

Zamora’s health was better while under house arrest, Gallagher said, but now his legal team is concerned about the environment he returned to.

“Being returned to those conditions is horrifying and unacceptable,” Gallagher said.

Nine press freedom and rights groups this week called for Zamora’s immediate release.

“We urge Guatemalan authorities to guarantee his right to a fair and impartial trial, free from undue interference and pressure,” they said in a joint statement.

Zamora’s case underscores a global trend in which politically motivated legal proceedings and trials against journalists are drawn out over a long time, according to Gallagher.

Gallagher’s other clients include jailed pro-democracy publisher Jimmy Lai in Hong Kong; Nobel laureate Maria Ressa from the Philippines; and the family of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was killed in Malta in 2017.

“What we’re seeing in Jose Ruben Zamora’s case in Guatemala, or Jimmy Lai’s case in Hong Kong, are these very prolonged proceedings which actually keep the person in prison and try to hold the international response at bay for as long as possible,” Gallagher said. “That’s a real problem.”