In the last week of the U.S. presidential campaign, candidate Donald Trump sued CBS News and filed a complaint with the Federal Election Commission against The Washington Post newspaper.

The cases are the latest high-profile conflicts between the former president and news outlets that he often accuses of bias.

Trump sued CBS over an interview of Vice President Kamala Harris on the network’s “60 Minutes” program that aired in early October. Trump had also agreed to give an interview to “60 Minutes” before backing out.

Filed in Texas on Thursday, the lawsuit alleges that the network aired two different responses from Harris about the Israel-Hamas war.

In a statement, CBS said “60 Minutes” gave an excerpt of the interview to the CBS show “Face the Nation” that used a longer section of her answer than what aired on “60 Minutes.”

But Trump’s lawsuit — which calls for a jury trial and $10 billion in damages — alleges that CBS violated a Texas law that prohibits deceptive acts in the conduct of business.

A CBS spokesperson told VOA the interview was not doctored. The lawsuit “is completely without merit and we will vigorously defend against it,” the spokesperson said in an email.

Trump on Thursday also filed a complaint with the Federal Election Commission alleging that The Washington Post illegally contributed to the Harris campaign.

The complaint alleges a social media ad campaign highlighting the newspaper’s critical coverage of the former president constituted “illegal corporate in-kind contributions and unreported last-minute independent expenditures.” Trump’s legal representatives allege the ad campaign meant the Post was “acting like any other partisan player in the election process.”

A Post spokesperson told VOA that promoted posts on social media reflect high-performing content from the newspaper

“We believe allegations suggesting this routine media practice is improper are without merit,” the spokesperson said in an email.

Gabe Rottman, policy director at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, dismissed the case against the Post.

“Advertising by news organizations is a legitimate, routine press function and receives strong First Amendment protections in the courts,” he told VOA in a text message.

Trump’s campaign and office did not reply to VOA’s multiple requests for comment on the recent legal actions or the former president’s press freedom record for this story.

Power to revoke broadcasting licenses

Trump has had a contentious relationship with some news outlets since running for president in 2015. Often referring to journalists as “the enemy of the people,” he has complained on social media and in speeches about ideological bias and unfair treatment of conservative voices, while also championing media that reflect his views.

He has pledged to jail journalists who do not name confidential sources on stories he believed to have national security implication, and suggested changing First Amendment protections to allow punishing people who burn the American flag or criticize Supreme Court judges.

Trump had previously threatened to revoke CBS’s broadcast license if elected. On his social media platform, Truth Social, he said “60 Minutes” had “created the Greatest Fraud in Broadcast History” and that CBS should lose its license because it is “corrupt.”

Following his September debate against Harris on ABC News, Trump called for that network’s broadcasting license to be revoked over what he described as “unfair” fact-checking.

And as president in 2017, Trump threatened to revoke NBC’s broadcasting license after the outlet reported a dispute between the then-president and his military advisers about the size of the nuclear arsenal.

In an October statement, the chair of the Federal Communications Commission, which issues licenses, said the FCC “does not and will not revoke licenses for broadcast stations simply because a political candidate disagrees with or dislikes content or coverage.”

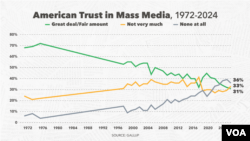

Many of Trump’s supporters applaud his attacks on the media, reflecting in part the steep erosion of trust in the press that public opinion polls have tracked among many Americans for years.

But media analysts say Trump’s attacks echo how leaders in countries like Hungary have undermined journalistic norms.

Clayton Weimers, the head of the U.S. office of Reporters Without Borders, or RSF, said the lawsuit against CBS “looks like a publicity stunt.”

But, he said, “It reinforces the very real threats that Trump has issued to use the U.S. government to punish media outlets he doesn’t like should he regain the White House.”

Leading up to and during his time as president, Trump published more than 2,000 posts on social media that the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker classified as anti-media. After Trump left the White House, his anti-media rhetoric has continued.

Between September 1 and October 24, Trump verbally insulted, attacked or threatened the media at least 108 times in public, RSF found in a study. RSF has not conducted a similar study about Vice President Harris because she does not make those kinds of anti-media statements, Weimers said.

“By just accepting that as a piece of this political moment, I do think there’s a risk that the American public has grown numb to how serious it is, what an aberration it is, and how dangerous it could be going forward,” Weimers said in a phone interview.

Trump’s public attacks against the media frequently play well with his supporters. At many of his rallies, the candidate often pauses after criticizing the media to give his supporters a chance to jeer at the reporters who are present.

Last month, Trump’s presidential campaign sent VOA a statement that Republican National Committee spokesperson Taylor Rogers originally provided to the conservative news site The Daily Caller. In it, Rogers described Trump as a “champion for free speech” and said that “everyone was safer under President Trump, including journalists” because of “commonsense law.”

Newspaper endorsements

Record-low distrust in media in the U.S. is what billionaire and Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos pointed to in an op-ed last week to explain why the newspaper would not make an endorsement in this year’s presidential election.

Days before the Post’s announcement, the billionaire owner of the Los Angeles Times said his newspaper would not endorse a candidate so as not to worsen political divisions.

For some media analysts, the decisions by the Post and the Los Angeles Times have only crystallized concerns about what a second Trump presidency would mean for press freedom in the United States.

Marty Baron, the Post’s former executive editor, said he thinks it would have been fine if the Post made this decision a year or two ago. But announcing the decision so close to the election was a “betrayal of core principles of the Post,” Baron told VOA in a phone interview.

“This is an invitation to further intimidation and bullying, and I think that that’s what we would likely see if Trump were to be back in the White House,” Baron added.

Margaret Sullivan, a media columnist with The Guardian who previously worked as a media columnist at the Post, said the decision does not reflect the newspaper’s ideals.

“This seemed to be a move from above that wasn’t about the content of the endorsement,” she told VOA in a phone interview.

Baron and Sullivan told VOA they’re concerned that the non-endorsement is a harbinger of what’s to come for press freedom if Trump is re-elected.

“I’m very concerned about intimidation of the press,” Sullivan said. “And frankly, I’m very concerned about the press preemptively acting like they’ve been intimidated when they have the ability to stand firm.”

Both of Trump’s legal challenges against the Post and CBS are expected to take weeks or months before they reach a resolution.